Insulin Resistance: A Simple Explanation of a Complex Problem

- Julien Boillat

- Dec 15, 2025

- 2 min read

Most people think insulin resistance happens only when you eat too much sugar. But insulin resistance is actually a whole-body problem, involving muscle, fat tissue, the liver, kidneys, blood vessels, and even mitochondria.

Understanding the basics helps make sense of fatigue, weight gain, inflammation, and long-term metabolic issues.

How insulin normally works

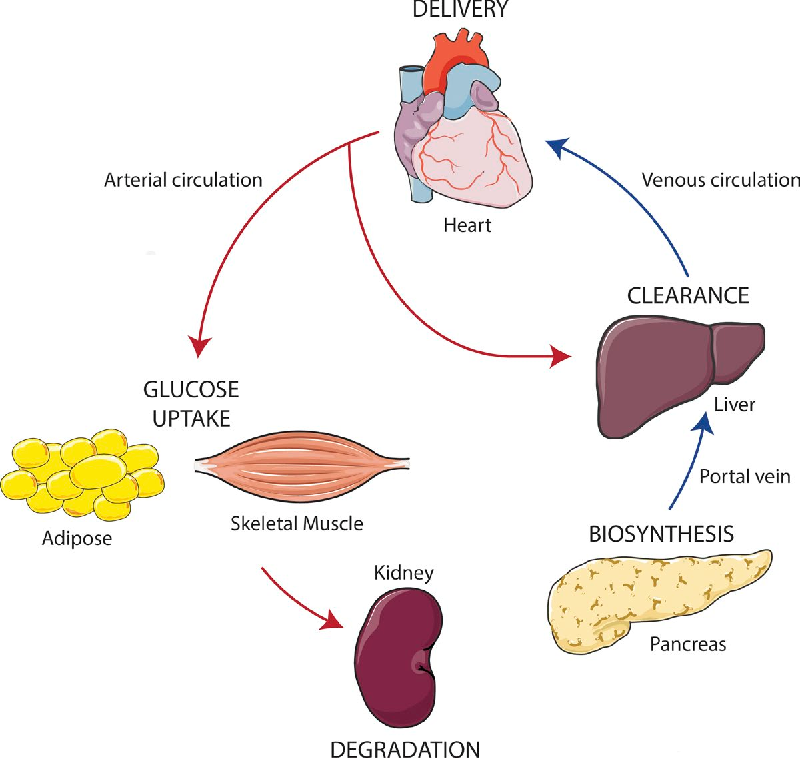

After a meal, insulin acts as a coordinator. It helps muscles take in glucose and store it as glycogen, tells fat tissue to store fat safely, signals the liver to stop producing sugar, relaxes blood vessels via nitric oxide, and briefly increases sodium reabsorption in the kidneys.

In a healthy system, insulin rises after eating, does its job, then falls back down.

What insulin resistance really is

Insulin resistance does not mean insulin stops working. It means the main pathway that allows glucose to enter cells becomes less efficient. To compensate, the pancreas produces more insulin.

This leads to chronically elevated insulin levels, which creates problems of its own.

Fat tissue becomes less sensitive to insulin and starts releasing free fatty acids into the bloodstream. Muscles absorb glucose less efficiently. The liver continues producing sugar when it should stop. As a result, the blood contains too much fuel—both sugar and fat at the same time.

Why this leads to oxidative stress

Muscle and liver cells absorb free fatty acids freely, even in insulin resistance. When too much fuel enters the cell, mitochondria become overloaded. They cannot burn unlimited glucose and fat at the same time.

This overload causes inefficiencies in energy production. Electrons leak from the mitochondrial system and form reactive oxygen species (ROS). These molecules damage mitochondrial function, increase inflammation, and further block insulin signaling.

Instead of a lack of energy, insulin resistance is a problem of too much energy arriving where it cannot be processed cleanly.

The kidney connection most people don’t know

The kidneys normally clear about one-third of circulating insulin. When insulin stays high all day, this clearance system becomes saturated, so insulin remains elevated even longer.

High insulin also makes the kidneys retain sodium and water, raising blood pressure. This activates the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). One of its hormones, angiotensin II, strongly increases oxidative stress.

Oxidative stress reduces nitric oxide in blood vessels, making them stiffer and less able to deliver oxygen and glucose to muscles. This worsens insulin resistance, closing a vicious circle.

The full picture

Insulin resistance is not a single-organ failure. It is a network problem:

Muscle absorbs glucose poorly.Fat tissue leaks fatty acids.The liver overproduces sugar.The kidneys retain sodium and raise blood pressure.Blood vessels lose flexibility.Mitochondria produce excess oxidative stress.

Each part reinforces the others.

The good news

Because insulin resistance involves many systems, it can improve when overall metabolic load decreases:

Regular movement, especially walking and muscle contraction, improves glucose uptake without insulin. Reducing ultra-processed foods lowers fuel overload. Allowing insulin to drop between meals helps restore sensitivity. Good sleep and stress management reduce hormonal pressure on the system.

Insulin resistance is not a moral failure or a sugar obsession. It is a physiological adaptation to chronic overload—and with the right signals, the body can recalibrate.

Comments